Timeless: A History of Chrono Trigger

How a Super Nintendo JRPG developed by a Dream Team of creators is still finding new fans 25 years later

Nobody likes to throw up at school.

But even if I could travel back in time to that fateful morning in early 1996, I wouldn’t change a thing.

I arrived at school groggy-eyed from staying up all night slugging coffee and working on Chrono Trigger fanfic. (Don’t ask me why a 12 year old was allowed to drink coffee all night, ask my parents.) My grade seven teacher had told us to create a sequel to Madeleine L’Engle’s classic fantasy novel, A Swiftly Tilting Planet. Given that series’s multiverse milieu, it was a perfect opportunity to swiftly tilt myself onto Chrono Trigger’s unnamed planet.

My story took place after the events of the classic Super Nintendo Japanese RPG’s best ending, and featured L’Engle’s characters teaming up with Chrono Trigger’s hero and anti-hero, Crono and Magus, in their search for Schala, the lost princess of Zeal.

I handed the assignment over to Ms. Matthews with pride and aplomb, exited stage left to the bathroom, and promptly threw up my breakfast.

It was a perfect day.

Chrono Trigger meant more to me than pretty much anything in those days. I’d discovered J.R.R. Tolkien’s novels the summer before, was devouring Terry Brooks’s Shannara series, and avidly playing Magic: The Gathering, but it was Chrono Trigger and its rival sibling Final Fantasy VI that turned my interest in fantasy books and games into a full blown obsession.

Like a combination of Secret of Mana and Final Fantasy VI, Chrono Trigger distilled everything that made the 16-bit console generation so beloved by its growing audience of JRPG fans, and so revered by gamers today. The genre would undergo a massive transformation after the release of Final Fantasy VII on the Sony PlayStation a couple of years later, marking Chrono Trigger as one of the last examples of console RPGs in the style popularized by the earlier Final Fantasy and Dragon Quest games. It truly was a melding of the generation’s best game mechanics, design philosophies, and creators.

This is a look back at 25 years of Chrono Trigger. The people who made it and played it. The memories. The ripples it left on time. It’s a celebration of one of gaming’s boldest and riskiest creative collaborations, and a reflection on how the unlikely coming together of A-list creators changed gaming forever.

So, let’s go back to where it all started. There’s a lot of history to catch up on.

Corridors of Time: About Chrono Trigger

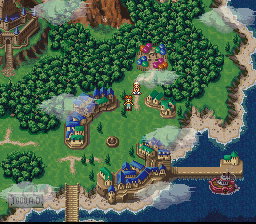

Chrono Trigger was created by JRPG powerhouse Square Enix*, best known for its Final Fantasy series at the time. As in those games, Chrono Trigger draws on its roleplaying roots to construct an adventure where the player explores various towns and dungeons, battles enemies in a menu-based combat system, and levels up their skills and attributes by collecting experience and ability points.

Players assume the role of Crono, a layabout swordsman who lives at home with his mom and appears to lack responsibilities or any role in society. At the Millenial Fair he bumps into a young woman named, er… Marle, and soon must follow her through a mysterious portal after she disappears. Along the way, Crono and Marle (who turns out to be the rebellious princess of Guardia) assemble a motley crew of inventors, robots, and frogs, and flit back and forth through time from 65,000,000 BC to the literal end of time itself as they seek a way to defeat an interstellar monster.

* Developer and Publisher Square Enix has been known by many names during its existence. At the time of Chrono Trigger’s release, they were known as Squaresoft and were still separate from friendly rivals, Enix. For clarity, I’ll abbreviate their name to Square regardless of the time period I’m discussing.

The Dream Team

Chrono Trigger has many endings, but one of its most elusive requires players to defeat Lavos with only Crono, or during a nearly impossible mid-game encounter you’re supposed to lose. Doing so returns the player to The End of Time — a hub area where they spend a lot of time — except now it’s filled with many of the game’s creators, including the Dream Team.

Chrono Trigger gained attention well before its release thanks to several well known Japanese creators heading its development. This “Dream Team,” as they’re referred to in the secret ending and by fans, consisted of Hironobu Sakaguchi (creator of Final Fantasy), Yūji Horii (creator of Dragon Quest), Akira Toriyama (creator of Dragon Ball), Nobuo Uematsu (Final Fantasy composer), and Kazuhiko Aoki (Final Fantasy IV designer).

But Chrono Trigger wasn’t simply a celebration of the Dream Team and the genre’s past successes. Impressively, over a dozen members of the Chrono Trigger creative team went on to direct a game later in their career. This includes Writer Masato Kato (Chrono Cross), Graphics Director Tetsuya Takahashi (Xenogears), Graphic Artist Yosuyuki Honne (Baten Kaitos: Eternal Wings and the Lost Ocean), and Event Planner Hiroyuki Ito (Final Fantasy IX). Many fans might also consider Yasunori Mitsuda an honorary member of the Dream Team in recognition of the legendary career he’s had since composing the majority of Chrono Trigger’s soundtrack. Chrono Trigger was a culmination of talent, passion, and creativity, and a celebration of Square’s legacy of transforming the console RPG genre.

At the time, Sakaguchi and Horii were twin pillars in the JRPG industry. On their own, they’d created the two most popular JRPG series of all time, and so combining their talents and experience on Chrono Trigger was a truly monumental moment in gaming history. It feels like the sort of project that could only happen during the mid-90s, before the games industry became the corporate juggernaut it is today. This was the JRPG equivalent of Street Fighter II teaming up with Mortal Kombat. AC/DC and Guns N’ Roses. The Yankees and the Red Sox. Unthinkable until it happened.

Hironobu Sakaguchi, creator of Final Fantasy

There’s an apocryphal legend about how 1987’s Final Fantasy was Square’s last gasp — a desperate clutching at life before it dissolved entirely after a string of failed games. Whether the now-legendary JRPG for the Nintendo Entertainment System truly saved the company or not, its impact on the genre, and gaming as a whole, is undeniable.

Inspired by his love for games like Ultima and Wizardry, a young Hironobu Sakaguchi was working part-time for Square on games like The Death Trap, and longing to take on RPGs. However, his enthusiasm for the genre couldn’t dent Square’s reluctance about the genre’s sales potential. Until competitor Enix (who Square would eventually merge with in 2003, forming Square Enix) and another rising star named Yūji Horii released Dragon Quest to great financial and critical success. Suddenly, Square wanted in on the game, and Sakaguchi was called upon to create a team for his long-desired project. He enlisted two other young developers, Koichi Ishii and Akitoshi Kawazu, to undertake Square’s most ambitious project.

Despite Final Fantasy’s scope and Dragon Quest’s success, Square was still reluctant to put too many eggs in an unfamiliar basket. But Sakaguchi was determined to give the game a chance at success.

“Initially, only 200,000 copies of the game were going to be shipped,” the Final Fantasy creator told Ed Fear in 2007. At the time, a new run of cartridges would take two to three months to produce, so initial shipment numbers put a soft cap on how many copies a game could realistically sell. Sakaguchi “argued and pleaded” to management that there was no chance for the game to be successful unless they printed 400,000 copies of the game. “But the costs were high, so as a company all they could think was ‘that’s a lot of money!’ despite having this great game.” In the end, Sakaguchi won, and Square printed 400,000 copies of Final Fantasy when it was released in Japan in 1987. It far exceeded even Sakaguchi’s estimates, building momentum after its first shipment, selling over 540,000 copies on the Nintendo Entertainment System, and spawning one of the most successful and recognizable JRPG series in history. This success cemented Sakaguchi as one of the most influential game creators in the world.

Yūji Horii, creator of Dragon Quest

A graduate of Waseda University’s Department of Literature, Yūji Horii worked as a freelance writer for Shonen Jump before winning an Enix-sponsored game programming contest with a game called Love Match Tennis. His victory inspired him to leave traditional writing behind to become a game designer, and he created a visual novel series called The Portopia Serial Murder Case.

After initial success with these visual novels, Horii made Dragon Quest, which also drew inspiration from games like Wizardry and Ultima. Alongside Final Fantasy, it laid the foundation for decades of JRPGs. Dragon Quest remains one of gaming’s most popular series, especially in Japan, and has sold more than 80 million units worldwide. Horii is still leading the franchise over 30 years later.

“Horii is a very quiet person,” Sakaguchi said in an interview, “but I think that’s because he is intently observing the people around him. He reads people well. And I think he uses that ability to help in creating his own dramatic scenarios. I didn’t realize that about him when I first met him, but I felt it strongly after we worked together on Chrono Trigger.”

Sakaguchi said there were no real fights between him and Horii while working on Chrono Trigger, but they did clash on a number of things. “Those confrontations gave us the opportunity to think very deeply about the game, though, so I think it was probably a good thing. Things that we at Square normally don’t pay much heed to were things that, in contrast, Horii always paid attention to. He gave me a lot to think about: if these were things that Horii was concerned about, then that means players must be too.”

“These two very different men brought together their very different visions of what RPGs can and should be, and… somehow, managed to reconcile these ideas beautifully,” said games writer Jeremy Parish for USgamer.

Determination: Chrono Trigger’s Development

Chrono Trigger was born in 1992 when Sakaguchi, Horii, and Dragon Ball creator Akira Toriyama traveled together on a computer graphics research trip to America, where the Super Nintendo had released just a year prior. “During the trip we decided that we wanted to create something together,” remembered Sakaguchi in a V-Jump preview video for Chrono Trigger, “something that no one had done before.

“We were really naive…”

“We got all fired up about it,” said Horii, a time travel story-fanatic who never missed an episode of classic television series Time Tunnel. “Normally you’d think things would have ended there, that we wouldn’t have been so excited…”

“That’s right,” agreed Sakaguchi, “we were really enthusiastic about it. Just talking about it was really exciting. However, once we decided we were going to do it for sure, we spent a year or a year and a half thinking about all the difficulties we’d encounter.

“We had almost given up when we received word from the producer, Mr. Aoki.

“He said ‘No, if you’re going to talk like that, please ask me. I definitely want to help make it happen.’”

Kazuhiko Aoki joined Sakaguchi, Horii, and Toriyama in 1993. After a four-day brainstorming session, the “Dream Team” had assembled an early plan for Chrono Trigger. The project started to ramp up, and Square brought on over 40 developers to work on Chrono Trigger, a huge number at the time.

“My life was made considerably more difficult thanks to this project,” remembered Aoki.

Originally, Chrono Trigger was meant to fall under the Seiken Densetsu (Secret of Mana, Trials of Mana) brand. Developed under the name Maru Island, the project was planned for the Super Famicom Disk Drive — a CD-ROM add-on peripheral for the Super Nintendo developed in partnership with Sony.

“The CD-ROM adapter was never completed,” explained Hiromichi Tanaka, Producer of Secret of Mana, in the liner notes for that game’s soundtrack. “Once everyone learned that the CD-ROM adapter was never going to see a release, they decided to abandon everything that had been planned for development since the very start, including Toriyama-sensei’s contributions, and decided to revise the project in order to make it release into a [Super Nintendo cartridge]. We said that we would wait for the CD-ROM to make a collaboration project with Toriyama-sensei, but when it was revised, it actually became an entirely different project with an entirely different direction. That was what later on was completed into the game we know as Chrono Trigger.” Perhaps this explains the similar designs shared by the main characters from Chrono Trigger and Secret of Mana. Both games were eventually released on cartridges for the Super Nintendo, and are two of the system’s most popular games.

Chrono Trigger was one of the Super Nintendo’s largest games, jumping from a 24Mb cart to an enormous 32Mb cart midway through development. It was Square’s first of that size, and Takashi Tokita, Director and Scenario Writer on Chrono Trigger, joked in an interview that they could have fit four copies of Final Fantasy IV on a single Chrono Trigger cart.

“[Chrono Trigger] being a time travel RPG, we really wanted to show different outfits and clothing for all the NPCs in different time periods, and we wanted to change the appearance of the towns… lots of details like that kept coming up as the development went on,” Sakaguchi said, explaining why the game’s storage capacity grew so dramatically.

“If I had to say, it was mostly used on extra music and graphics,” said Graphic Director Yasuhiko Kamata, “adding branches to the tree, so to speak.”

“Yeah,” agreed Kato,” the majority of it went to graphics. Some was used for scenarios, events, and some extra dialogue too.”

“I think about 6 of the 8 megs was used for graphics,” said Kamata.

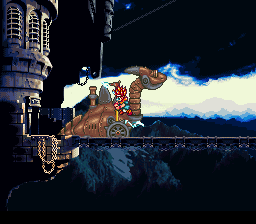

“We had done our best to fit all the graphics into 24 megs, but it turned out to be too much,” remembered Kato. “We couldn’t fit all the scenarios we wanted in either. It’s thanks to those extra 8 megs that Magus’ castle looks so fantastic. Those setpieces couldn’t be done just by reusing sprites and tiles from other dungeons. Well, we always try to reuse things where we can, like that moon. At the planning stages of a development, when your mindset is much more conservative with regard to memory, you can’t really create elaborate setpieces and scenes. So that 8mb came at just the right time.”

Magus’s castle is the setting for Chrono Trigger’s first act climax, and anyone who played the game at the time remembers with vivid detail the feelings they experienced as the camera panned slowly up towards its peak. Up to this point, even the most sophisticated JRPGs like Final Fantasy VI used normal tile-based assets for set pieces, so Chrono Trigger’s bespoke, hand-crafted approach was (and remains) stunning.

Tokita thought they’d probably managed to squeeze every last bit out of the Super Nintendo. A quarter century later, it’s safe to say he was right.

“The way Square develops games is different from other companies,” revealed Programmer Katsuhisa Higuchi in a 1995 interview. He paints a vivid picture of a team where even the “planners” had programming experience and could “create actual in-game data themselves.” He saw a looming problem, though: As the team grew, how would they effectively leverage the new members who didn’t know how to program?

“As someone who recently joined Square, I’ve thought about that a lot myself,” writer Masato Kato followed up. “If you try to join Square just as an ‘idea man’, then you’re going to have a very hard time.”

“With all these planners who know about programming, though, it can be tough for a programmer working at Square!” Higuchi joked. “Say you get some task and think, ‘man, this is going to be annoying to code.’ If the planners didn’t know anything about software you could just say ‘I can’t do it.’ But at Square we can’t say that!”

This level of perfectionism wasn’t new for Hironobu Sakaguchi, who had recently completed work on Final Fantasy VI, but he found himself taking on a new role with Chrono Trigger that caused headaches for programmers like Higuchi.

“I was a really strict boss during the development of Chrono Trigger,” he said in a 2014 interview with Famitsu. “Every morning I’d gather everyone together and make them give me status reports.” It was unlike anything he’d ever done with the Final Fantasy series.

“This was the biggest game we’ve worked on at Square in terms of memory, with about 50–60 people involved in the development,” said Tokita. “With that many people, it was very difficult to convey even a simple message to everyone.” Until that point, development teams at Square generally maxed out at about 25 people. Famously, they had to pull many developers off a Super Nintendo-based Final Fantasy VII project to help finish Chrono Trigger. Among those pulled over was Yoshinori Kitase, who eventually earned a Director credit on the game, and most recently co-directed Final Fantasy VII Remake for the PlayStation 4. According to Tokita, Chrono Trigger’s development team was “a couple hundred” people by the end, an unprecedented size during the 16-bit era.

“In that sense,” said Aoki, “Chrono Trigger represents a real achievement in terms of teamwork and everyone working together at Square.”

Chrono Trigger could have collapsed under the weight of its ambitions, but instead the All Star team of creators, artists, developers, and planners unified under a shared vision — resulting in a creative commercial product without a modern day parallel.

“Chrono Trigger possessed the simplified accessibility and relatable character writing that continues to define Dragon Quest,” said Jeremy Parish for USgamer, “but it married these elements to the scale, pomp, and experimental design that had become Final Fantasy’s stock in trade.”

Chrono Trigger became sacred property after the 2003 Square and Enix merger, Tokita told GameInformer in 2016. Trying to exceed legendary source material like Final Fantasy and Dragon Quest was “very difficult,” he admitted, but the all-hands-on-deck approach not only allowed the Dream Team to match the project’s ambitions with talent, it wound up producing one of the most beloved games of all time. “It was kind of like a grand festival,” said Tokita, “it was really fun.”

World Revolution: Chrono Trigger’s Release

Chrono Trigger was released on March 11, 1995 in Japan, and just a few months later in North America. It was selected by Electronic Gaming Monthly as their “Game of the Month,” receiving a score of 37/40 from its four reviewers. Game Players gave it a 95% and lead reviewer Jeff Lundrigan said:

This was designed by many of the same people who put together both the Final Fantasy and Dragon Warrior series, and it shows. They’re constantly playing little games with RPG play mechanics and other conventions of the genre. I don’t want to give anything away, but if you do everything the way you’re used to, the game is going to come up and surprise you every now and then.

…

The bottom line is that this is a must-have for RPG fanatics and dabblers alike. Stop reading, go out, and buy it.

Chrono Trigger sold over 2,000,000 units in Japan, but, despite glowing reviews, managed to sell fewer than 290,000 in North America — far less than Final Fantasy VI’s 450,000. Just two years later, Final Fantasy VII would blow the roof off the Japanese RPG market, selling over 3,000,000 units in North America alone, and turning the genre into one of the hottest in gaming.

Chrono Trigger’s relatively low sales in North America didn’t stop it from becoming both a critical and fan darling over the years. It placed 26th on Electronic Gaming Monthly’s 2001 “Top 100 Games” list, and more recently earned top spot on ResetEra’s community-voted Top 101 Essential RPGs list and was named the best RPG of all time by USgamer.

Mystery of the Past: Story and Theme in Chrono Trigger

I got Chrono Trigger for my 12th birthday, just before Christmas ’95, and have vivid memories of exploring its gorgeous world, and spending the entirety of winter break chasing down the evil wizard Magus. Immediately upon completing the game a few weeks later, I loaded up a New Game + file and started the adventure over again. I remember the swell of pride as I bragged to my mom that I managed to make it to the Kingdom of Zeal in only two days this time, when it took me two weeks on my first play through. I kept playing and playing. Caught in a time loop of saving the world.

Because Chrono Trigger’s was a world I wanted to save on repeat.

From singing robots deep in the Ocean Palace, to two fiends playing pass with one of their friends as the ball, Chrono Trigger implemented a style of comic humour familiar to fans of Akira Toriyama’s Dragon Ball. This set it apart from the more serious Final Fantasy, and it managed this without sacrificing emotional nuance. Finding this balance between goofy humour and existential threat created a world that felt truly in crisis but worth the effort of saving. The enemies threatened Crono’s party in battle, but you also saw their domestic life in 1000 AD’s Medina Village, or empathized with the plight of the reptites in 65,000,000 BC, when their very existence was threatened by Lavos’s arrival.

Chrono Trigger’s world was diverse and interesting, full of different environments spread throughout time. Each era had their own conflict, and they all added to the overarching theme of communities banding together to fight for humanity’s greater good, to cast aside the pursuit of personal power and consider how greed impacts generations to come. In a world facing rapid climate change, it seems like we still have many lessons to learn from Chrono Trigger’s heroes.

Where contemporaneous games like Final Fantasy VI or Phantasy Star IV immediately thrust their protagonists into the thick of conflict, centring the heroes as already influential (or at least important) players in the game’s early plot, Chrono Trigger’s core of Crono, Lucca, and Marle, have very little in the way of personal stakes tied up in Lavos’s defeat.

After being whisked 400 years into the past by an errant time portal, Marle is mistaken for her ancestor, Queen Leene. This ends the the Kingdom of Guardia’s search and rescue operation. However, if the real Queen Leene, who has been kidnapped by the villain Yakra, is never found, Marle will never be born. A time paradox ensures, and Marle literally disappears. It falls to Crono and Lucca to resolve this by saving the real Queen Leene. Afterwards, back in the present, Crono’s accused of kidnapping Marle. He’s put on trial, and then, in a twist of fate, the trio of youngsters are cast into the future during Crono’s prison escape. To this point, Crono and Marle have both faced small scale personal threats, but it’s not until they activate a computer in 2300 AD’s Arris Dome and learn about Lavos’s destruction of the world in 1999 AD that the game’s overarching conflict is revealed. Horrified by the looming devestation, Marle takes on the singular mission of defeating Lavos and saving the future by changing the predetermined past.

Crono, Lucca, and Marle could sit pretty in 1000 AD and live a good life. Lucca could keep inventing things far beyond the technological level of the period. Marle could thrive as a restless princess. Crono could, uh, hit the gym? Point is, nothing would change for them if they chose to stay at home. They live during a time of peace and prosperity. Life is good and remains good — idyllic, even — for the next 999 years. However, Marle’s altruism fuels their motivation, and they pursue Lavos not for personal benefit, but for the genuine greater good of humanity. While each member of Chrono Trigger’s small but diverse cast has their own story and motivations, the greater story is one of fighting for community. Crono, Marle, and Lucca create the plot of Chrono Trigger with their actions, instead of being dragged along by forces larger than themselves, as is so common in JRPGs.

One might notice, however, that it’s Marle who drives the plot forward — not Crono, the main player character. Crono’s silence is one of the game’s most defining narrative features, especially when compared to Square’s flagship JRPG series, and there was much debate among the Dream Team about how to approach Crono’s role in the story.

“We argued a lot with Yūji Horii over whether Chrono [sic] should speak or not,” admitted Yoshinori Kitase in an interview around the game’s release. The heroes of Horii’s Dragon Quest series are always silent. “Horii said that the protagonist of an RPG must never speak. And at Square, opinions were divided on the issue. We eventually decided to go with a hero who doesn’t talk, but once that decision was made, it greatly changed the way we were constructing the event scenes.”

Both approaches have their merits, said Tokita, but Aoki pointed out that a speaking protagonist often comes with risks. “[It] causes the player to take a stance on whether he likes or dislikes this hero,” he said. “At the same time, if you make your hero do bad things, players will hate him. That’s why protagonists in most RPGs who do talk have mostly had bland, inoffensive dialogue. From that perspective, I think there’s a definite advantage in having a protagonist who does not speak at all.”

“Definitely,” said Kitase. “It’s a fact that by having the hero not speak, the player can more easily get invested in the game. That was part of the thinking behind our decision.”

Having a silent protagonist forced Chrono Trigger to lean heavily on its supporting cast for personality and exposition, and the game delivered in spades, according to Peter Tieryas of Kotaku.

“In almost every scene, the characters are at the forefront,” he said in “Chrono Trigger’s Campfire Scene Is A Meditation On Friendship, Regrets, And Time Itself.” “Whether it’s Crono and Marle’s budding relationship, or Frog’s attempt to uphold his honor after his failure at the hands of Magus, and even Magus’s twisted past that has taken him throughout history in an attempt to take revenge on Lavos. The dialogue always gives insight into what the characters are thinking both on a conscious and subconscious level, betraying emotions they’d rather hide.”

When Chrono Trigger opens, its young heroes insert themselves into the conflict, but as the hours tick by, they become inexorably entwined the plot, until, by the time you’re wrapping up the game’s myriad optional side quests near the end of the game, each mission you take part in concludes one of the game’s personal storylines.

Chrono Trigger’s main cast are all individually motivated, but often their personal quests and personalities find balance with others in the adventuring party. Lucca’s aloofness sits comfortably beside Ayla’s bold determination; Frog seeks atonement for past failures, while Marle pursues the future with reckless momentum; Robo’s search for self reveals a nebulous sense of purpose, sharply contrasted against Magus, whose purpose has been honed to a singular point of infinite sharpness, piercing his entire identity.

“Every time I play the game, I feel like I’m time traveling to my past to spend time with old friends,” said Tieryas. “I love the optimism thematically inherent in Chrono Trigger, a feeling that there’s always hope.”

“Ever since I was a boy I’ve liked Sci-Fi,” said writer Masato Kato in Chrono Trigger Ultimania, “and within that really loved time travel.” Kato, who went on to write and direct Chrono Trigger’s sequel, Chrono Cross, and is often cited for the game’s overarching story, joined the project mid-way through during the first expansion of the development team. Surprisingly, given his fondness for the trope, Kato initially pushed back against the idea of time travel in Chrono Trigger.

“The person who initially suggested we do a time travel piece was actually someone from outside of the project, and I objected to it at the time. Because I liked time travel stories so much, I knew that dealing with this subject in a game carried an unusually high danger of becoming a boring, unappealing work. However, my opposition to going with time travel was in the minority.”

He was afraid that a game about time travel had a high likelihood of not being done well, or become tiresome for the player.

“With time travel, you have to develop quests that allow the player to visit different worlds back and forth along the timeline,” he said. “This being the case it needs to be made easy to understand even more so than other kinds of games, or else the player can get lost and have no idea where to go or what to do next. You have to make it so that the player can clearly visualise causes and effects. On the other hand, there’s also the pitfall of it becoming a boring ‘plant the flag’ kind of game. These are the kinds of things I had to take into consideration.”

Brink of Time: Time Travel (or not) in Chrono Trigger

The Chrono series, including Chrono Trigger, Radical Dreamers, and Chrono Cross, features a complex timeline with many dead ends, paradoxes, and alternative realities. However, that’s mostly thanks to Chrono Cross, and Chrono Trigger itself is a fairly linear experience outside of the side quest-heavy final act. It leaves temporal paradoxes about time travel alone after the scenario early in the game when the team’s arrival in 600 AD throws history in the blender. Otherwise, it’s not really a game about time travel.

Chrono Trigger’s most shocking and memorable plot twist occurs at the game’s midpoint when, in a moment of Christ-like self sacrifice, Crono throws himself in Lavos’s path, saving his team (and the world) from certain doom, but at the expense of his own life. JRPGs had played with seismic plot twists before, as recently as Final Fantasy VI’s World of Ruin, just a year prior, but the impact of losing the game’s hero and your strongest combatant was staggering.

“As you might expect for a game about time travel, death is not final,” said Chris Kohler on Kotaku. The player can revive Crono through the use of the titular Chrono Trigger item, but it’s completely optional. You can beat the game without ever reviving Crono. It’s even possible for an enterprising player to complete the game with the hero dead, and their party led by the main villain of the game’s first half: the wizard Magus.

“In this back half of the game,” said Kohler, “now that the player fully understands the mystery of the story and can therefore be let off the leash, we start to see the game play around a little bit more with the possibilities of time travel in storytelling.” He points to a subplot where the player must revive a forest by leaving a robotic character named Robo behind in 600 AD and retrieve him in 1000 AD. It’s a mere skip in the time-travelling Epoch for the party, but 400 years have passed for Robo.

“Chrono Trigger in no way attempts to reckon with the concept of the ‘butterfly effect,’” said Kohler, “the idea that the tiniest of changes could have massive ripple effects that alter the entire face of the world. Change one thing about the past [in Chrono Trigger], and exactly one thing changes about the future.”

There’s a lot of cause and effect in the game’s plot, but very little player choice or variable outcomes. Either you take the action the game wants you to take — and receive the reward — or you don’t. You fight Magus, or you don’t. Choices can lock you out of content in rare instances, but rarely provide a unique play experience.

“With time travel as our theme, you could have the same character be a totally different person if they belonged to a different timeline,” Hironobu Sakaguchi told Famitsu in 2014. “That was the planners’ original idea, but I said it was no good. I said that even if the player changes history, when you return to your original time, it should be the same Marle there that you knew from before.”

“I hadn’t thought about it that deeply,” Kitase replied, “but Sakaguchi insisted that we should focus on building these characters consistently and thoroughly. It left a big impression on me.”

Kato and Horii initially wanted Crono’s mid-game death to be permanent, according to an interview in Chrono Trigger Ultimania. The plan was for his teammates to replace him by skipping back to a point in 1000 AD just before the game begins, to retrieve an alternate timeline version of their friend. This is the sort of paradox you’d expect from a game about time travel, but it’s not Chrono Trigger’s modus operandi. (Unless you’re Chrono Cross, but that’s a whole other essay.) Instead, in the final version of Chrono Trigger, the player travels to the exact moment of Crono’s sacrifice and replaces the “real” Crono with a clone doll, dramatically altering one of the game’s most heart wrenching moments.

“By focusing on linear gameplay inside dungeons, the developers of Chrono Trigger were able to give players the freedom to choose to experience or not experience entire sections of narrative, in any order they wish,” described Gamasutra’s Victoria Earl in “Chrono Trigger’s Design Secrets.” “This modular style of narrative allowed the developers to create linear character arcs and subplots while still giving players freedom within the overall narrative.”

In Chrono Trigger, time travel is always a solution, never a problem.

Far Off Promise: Chrono Trigger’s Innovations

If Chrono Trigger was a coming together of design philosophies and knowledge, a meeting of ideas, dreams, and a culmination of the first JRPG golden age, it was also the start of something new. Chrono Trigger polished many well-used ideas until they were positively gleaming, but also innovated in ways that fundamentally changed how JRPGs were constructed, and what gamers expected from the genre.

Foremost among these was the New Game + system, which allowed me to reach the Kingdom of Zeal in a mere two days on my second play through. It’s a familiar concept to gamers in 2020, allowing the player to start the game over while retaining their previously levelled up characters, their inventory of high-powered weapons, and their spellbook bursting with magic, but the term itself originated with Chrono Trigger.

For any player who beat the game once, a new option appeared on the file select screen called “New Game +.” Selecting this allowed the player to choose a save file and continue their game — not from the moment where the save left off, but from the game’s opening scene, with Crono’s mother waking the erstwhile hero from a heavy slumber. A quick glance in his pockets reveals Crono’s most formidable weapons, and a trip to the Millennial Fair to fight the cat robot Gato proves a cakewalk. New Game + hands the player a ludicrously powered team, and the tools to cruise through the story in a brisk dozen hours.

Though the concept of gameplay changing on subsequent play throughs dates all the way back to games like Pac-Man and Donkey Kong, Chrono Trigger popularized and coined the concept for JRPGs. Coupled with the genre’s narrative focus, New Game + gave players a more appealing alternative to a 30+ hour grind to get the most out of their game. I’ve played through Chrono Trigger more times than any other game, thanks in large part to how quick and appetizing New Game + makes subsequent play throughs.

With a sufficiently levelled party, a player can complete Chrono Trigger very quickly, but the original plan, according to Sakaguchi was to reduce the number of battles and encounters to the point that even a first play through could be completed in about eight hours. Despite Horii’s wishes for it to be accessible to all players, Chrono Trigger isn’t an easy game, but perhaps we can see the Dragon Quest creator’s original vision in New Game + play throughs, where combat takes a back seat to narrative and exploration.

Before you ever get to this stage, however, a fresh play through highlights many of Chrono Trigger’s other innovations, including its battle system, which features the player’s party of three characters fighting enemies directly on the dungeon maps, and teaming up to unleash joint magic techniques to great effect.

It was Yūji Horii who pitched the idea of these “renkei” attacks (which means “collaboration” in Japanese.) The development team loved the concept, but not his suggested name, so they were renamed “dual techs” and “triple techs,” signifying how many of the party members were involved. These combination attacks offered players an enormous amount of variety in party construction and combat strategy.

“We’d spent so much time getting the individual character animations to look good, and everyone really enjoyed that,” said Battle Planner Toshiaki Suzuki in an interview. “We thought it would be even more fun if the characters moved in unison, working together.”

Yoshinori Kitase described in an interview how they heavily experimented with multiple battle styles to find the best fit for the game, including a system similar to the one in the Final Fantasy series, “where you’re suddenly drawn into combat while walking around a map.”

The system they settled on features battles taking place directly on the dungeon maps without a graphical transition. This allowed them to create many unique scenarios throughout the game. “For example,” said Kazuhiko Aoki, “you’re walking down the path and your foot gets caught in a vine, and then enemies that were hiding in the bushes suddenly appear! We created over 100 of them — all by hand. Like the event system, the battle system was another way for us to make Chrono Trigger more exciting and dynamic. For us creators who had to make all these scenes though, it was very difficult.”

Concepting and programming all these scripted battle sequences “took just as much time as the story and events,” revealed Tokita. “We really squeezed every last drop of brain matter from our heads to come up with all those different battle lead-ins.”

The effort was worth it, however, leaving Chrono Trigger with one of the most unique battle systems in any JRPG. By allowing the player to remain on the dungeon map, Chrono Trigger’s battles not only retained a sense of place within the over world, they were also extremely quick to start and conclude, with no time wasted on transition screens or load times.

“By using this method, Chrono Trigger gives freedom to both developers and players,” said Victoria Earl of Gamasutra. “Developers have the freedom to craft exactly when, where, and what players have to fight while progressing through the game.”

“In the Final Fantasy series,” said Aoki, “when you get into a random battle, the first thing you think is, ‘oh, it’s these guys again.’ But in Chrono Trigger, you don’t have to fight if you don’t want to: you can sit back and observe the enemies’ behavior, and see their personality. Some act like little show-offs, others are all weird — you can learn about them before you fight them.”

This approach also forced the developers to polish the character progression system, because there was no opportunity — or need — to grind levels. Players were left with a smooth experience with few frustrations or difficulty spikes.

This wasn’t an accident, according to Sakaguchi. “We actually struggled a lot on how difficult to make the game,” he remembered. Yūji Horii’s instinct to make Chrono Trigger easier for new players was the first step for a team trying to balance on a knife’s edge. On one side was a gameplay-style beloved by fans for its systems and number crunching, and on another you had new players who were looking for something approachable and easy to understand.

“Chrono Trigger is basically the antithesis of the classic PC gamer concept of the RPG,” said USgamer’s Jeremy Parish in 2017. “And yet it manages to be a masterful representation of the genre by playing up its own strengths. It doesn’t attempt to adhere to a genre formula or someone else’s rules. Instead, it’s a middle ground between two different schools of console RPG design thought, a brilliant compromise that manages to be entertaining for newcomers and pro players alike.”

A Dancing World: The Art of Akira Toriyama

Capturing the essence of legendary manga artist Akira Toriyama in Chrono Trigger wasn’t easy, according to Sakaguchi. “The sense of dancing you get from exploring Toriyama’s worlds is a little more difficult to capture than I initially thought,” he admitted in Chrono Trigger: The Perfect. “There were times that I felt under pressure to make as much of a Toriyama-style world as possible, but contrary to my expectations I found that it was okay to play around with Toriyama’s universe. It felt like anything was possible.”

Akira Toriyama is best known for creating Dragon Ball and Dragon Ball Z, hugely popular action-based manga and anime series with a penchant for humour. Horii previously worked with Toriyama on the Dragon Quest series, but Chrono Trigger offered a greater opportunity for the artist’s brand of humour than the genre’s flagship series, especially because Chrono Trigger was a brand new work, unfettered by the expectations that defined Dragon Quest and Final Fantasy.

“Even in really serious scenes there’s a lot of silliness,” said Horii, referring to a scene early in the game where Crono and Lucca walk over a human bridge of enemy soldiers after a large explosion. “We had a lot more freedom than we would with Final Fantasy or Dragon Quest. We weren’t worried about the feel of the world; it would be whatever we ended up making.”

Though Toriyama’s influence on the project and status on the Dream Team are undeniable, his involvement was limited to early portions of the game’s planning and development. “He only did the character illustrations and concept art,” said Kitase in an interview archived on Shmuplations, “but those illustrations gave us a lot of inspiration. They gave us ideas about the world of Chrono Trigger and the character dramas. It’s really amazing how many ideas we got just from looking at them.”

“His images conveyed a sense of the world, an atmosphere, a vibe — I used them to unify the rest of the visual design,” said Graphics Designer Matsuzō Machida, who eventually went on to create the Shadow Hearts series on PlayStation 2.

“Unfortunately he only drew characters from the front,” added Character Graphics Designer Hiroshi Uchiyama, “so we didn’t know what they looked like from behind. It was kind of a problem… we just had to guess.”

Courage and Pride: The Music of Yasunori Mitsuda

While Chrono Trigger was developed by a literal dream team of experienced game makers, perhaps its most notable contribution came from a young musician named Yasunori Mitsuda. As Chrono Trigger was spinning up, Mitsuda was working as a sound composer, and had created sound effects for Square’s Final Fantasy V. But he had his sights set on something much more grand.

“I wasn’t being paid very well at the time,” Mitsuda told 1UP.com in 2008. “I wasn’t even able to pay the bills, so I started thinking to myself that I had no other choice. I felt the situation was unfair. ‘If you’re not going to let me create music, then I’m going to quit,’ is what I basically said to Sakaguchi. So he responded: ‘In that case, you should do Chrono Trigger — and after you finish it, maybe your salary will go up.’”

While Mitsuda admitted that his salary didn’t increase all that much, the project did give him the space and opportunity to realize his dreams. Working on Chrono Trigger became more than a job to Mitsuda: it became an obsession. “I’d camp out in the studio the entire time,” he said. “I’d keep everything on all the time and I’d drift off to sleep. If I was sleeping and a melody came to me, I’d jump right up and be able to work on it.”

Mitsuda worked himself dry, and eventually ended up in the hospital due to stomach ulcers. At that point famed composer Nobuo Uematsu, known for his work on the Final Fantasy series, stepped in and completed the soundtrack’s final few tracks.

Masato Kato remembered worrying about Mitsuda. “My first thoughts were like, ‘Man, who is this young, optimistic fella’ who’s getting all hyped up by himself?… Please don’t tell me he’s the only one working on our sound team… Is he REALLY going to be OK?’ Those were the kinds of feelings that popped into my head. No, I’m not kidding.”

Mitsuda was allowed to leave the hospital to join his team mates to celebrate Chrono Trigger’s completion, a moment he remembers fondly in an interview with Weekly Famitsu. “When the entire staff gathered around to watch the ending, I wound up crying … I think all of us put a lot of our emotion into the game.”

After his success on Chrono Trigger (and physical recovery), Mitsuda composed many other highly regarded soundtracks, including Front Mission: Gun Hazard, Xenogears, Xenoblade Chronicles, and perhaps his greatest work: Chrono Cross. Mitsuda gambled on himself early in his career, and the payoff has been decades of beautiful music across a wide library of classic games.

“Flexibility,” said Kato when asked about Mitsuda’s greatest strength. “I think his works speak for themselves in that aspect.”

Mitsuda’s work has spawned numerous arranged albums over the past 25 years, including his own To Far Away Times, a collection of arrangements from Chrono Trigger and Chrono Cross, and The Brink of Time, an album of jazz-influenced rearrangements. A number of fan arrangements have also been released, notably the immense Chronicles of Time — which features 75 tracks from over 200 musicians, including Eight Bit Disaster, William Carlos Reyes, and Dale North.

As we celebrate Chrono Trigger’s 25th anniversary, it’s a wonder to consider that Mitsuda, now only 48 years old, was in his early 20s when he created one of the most universally praised video game soundtracks of all time.

To Far Away Times: Chrono Trigger Through The Ages

Released during the Super Nintendo’s twilight, Chrono Trigger rode the wave of Final Fantasy VII’s success on the PlayStation to a re-release on Sony’s JRPG juggernaut in 1999. Though the PlayStation was undeniably more powerful than Nintendo’s 16-bit console, this North American release of Chrono Trigger was plagued by long load times due to the way the emulated game injected Ted Woolsey’s English translation over top of a Japanese ROM in real time. With the upcoming North American release of Chrono Cross in August, 2000, this should have been a can’t miss opportunity to get an audience of newly-minted JRPG fans excited for one of the Super Nintendo’s best games, but this PlayStation port ended up being a tough sell, even bundled with a retranslated version of another Square classic, Final Fantasy IV.

Its sequel, Chrono Cross, released to critical success in North America and Japan, earning a respectable 36/40 in Weekly Famitsu and a perfect 10 from Andrew Vestal at Gamespot. It shipped 1.5 million units worldwide and received a “Greatest Hits” release in North America.

Despite its growing status among JRPG fans, and with the price rising steadily on the secondhand market for used Super Nintendo carts, Chrono Trigger would not see another rerelease until Square announced in July, 2008 that they were remastering the game for Nintendo’s hugely popular DS system. This version included a new localization, and added new weapons and armour for each character, a couple of end game dungeons, and a new ending connecting Chrono Trigger to the events in Chrono Cross. It’s still considered by many fans, myself included, to be the definitive version of the game.

2011 saw a mobile port of Chrono Trigger and a release on the Nintendo Wii’s Virtual Console service. The mobile ports, available on major smartphone platforms like Android and iOS, were criticized for poor UI integration and general lack of polish, but for many gamers without access to the original carts or a Wii, they were the most accessible way to play the game for many years.

In 2018, Square released a PC version of Chrono Trigger with little fanfare. Despite the low profile release, the port was skewered by fans and critics alike for its ugly graphics, mobile-like UI, and general lack of features. Instead of resting on its laurels, however, Square released a series of patches over the next several months to address the major criticisms, and the PC version is now considered a competent, accessible, and affordable way to play the game.

Chrono Trigger has not received a console release since it appeared on the Virtual Console. It was curiously absent from Nintendo’s Super Nintendo Classic Edition, which featured several prominent Square games, including Final Fantasy VI and Maru Island sibling, Secret of Mana. One can’t help but feel, however, that a game with Chrono Trigger’s near-holy status deserves an undeniably definitive version for fans to enjoy and discover for years to come.

One Gate Closes, Another Opens

Chrono Trigger can’t change the past, but it has earned a place in the future as one of the most influential video games of all time.

Just a couple years after Chrono Trigger’s release, Final Fantasy VII took hold of the JRPG genre and changed it in uncountable ways, leaving games in the 16-bit style, like Grandia or Breath of Fire IV, few and far between. But in recent years, Chrono Trigger inspired Square to spin up Tokyo RPG Factory, which specifically focuses on making Japanese RPGs modeled on the 16-bit era, and has been cited as a direct inspiration for western indie RPGs like Cosmic Star Heroine and Sea of Stars. The kids who grew up playing Chrono Trigger on their living room Trinitrons are now the developers and creators making some of today’s most exciting games.

Among them is Thierry Boulanger, Creative Director on Sabotage Studio’s Sea of Stars. “[My friend and I] played it for three years straight,” said Boulanger when I spoke with him for this piece. “The magic that unravels just catches you off guard.”

Chrono Trigger has many lessons for game designers, Boulanger continued, citing its lack of random encounters and Horii’s emphasis on exploration and adventure over level grinding. “[In other JRPGs,] it’s one task after another,” he said. “You’re constantly looking forward to finishing what you’re doing because you want to get to the next beat. Whereas in Chrono Trigger, wherever you are in the story, the big [story] arc is clear. It was so daring how they had so many cool concepts, but they would use them for only one small part of the game.”

“We were actively trying to imitate Chrono Trigger’s visual style,” said Robert Boyd of Zeboyd Games when I asked how Chrono Trigger influenced his 2017 RPG, Cosmic Star Heroine. “I feel like the biggest influence for us has been with Chrono Trigger’s pacing. It is constantly throwing the player into impressive setpieces and exciting new plot developments and that is something that we’ve tried to do with our games as well.”

Each game element built on what came before it in a way that was unusual for JRPGs at the time, and hinted at what was to come with Final Fantasy VII a few years later. “The hunt for the Masamune felt like it could be a whole game,” said Boulanger, and each premise in the game stood on its own, while also being part of the larger arc. “It feels like it could have been eight games,” he laughed. “But they distilled, instead of diluting. It’s super dense in terms of pacing.

While today’s indie developers are influenced by Chrono Trigger’s innovations, the Dream Team never reunited to work on a sequel. Masato Kato and Yasunori Mitsuda teamed up on Radical Dreamers, a Japan-only visual novel, and again for Chrono Trigger’s official sequel, Chrono Cross, but the series stalled after that game’s 1999 release.

Despite Chrono Cross’s respectable sales numbers and success with the mainstream games media, it proved divisive among fans for its treatment of Chrono Trigger’s plot and characters, its dramatically different gameplay systems, and its opaque and convoluted plot. It’s become a bit of a truism among Chrono fans that Chrono Cross is a great game, but a bad sequel.

“Chrono Cross is a somber and meditational work, exploring destiny, fate, and decisions in a way that is more philosophical in nature than Trigger,” said Kotaku’s Peter Tieryas in his piece “Chrono Cross Was A Bad Sequel, But A Brilliant Game.” “Cross lacks the quirky humor that Dragon Quest’s Yuji Horii usually brings as well as Akira Toriyama’s anime aesthetic. You need to not only shed expectations, but almost put aside Chrono Trigger entirely to appreciate what an incredible feat Cross is.”

Because of these factors, and Chrono Trigger’s release before Final Fantasy VII blew the top off the games industry, Chrono Cross failed to build on Chrono Trigger’s promise, and a third game in the series never materialized.

Considering Chrono Cross’s massive departures from its prequel, it’s almost impossible to imagine what a third Chrono game would look like, but Takashi Tokita revealed to IGN in 2017 that he had spent time on a sequel called Chrono Break. It was canceled before he accomplished anything. However, his 2015 mobile game gives fans a hint of what might have been. “The overall idea for the title was carried over to [Final Fantasy Dimensions II],” he said. “Aemo’s character setting and the balance between the three characters at the beginning…these were based on the original concept [for Chrono Break] but were reworked for this title.”

Hionobu Sakaguchi revealed at a 2014 Pax Prime panel called “Hironobu Sakaguchi Reflection: Past, Present, Future of RPGs” that he fought for Chrono Trigger to become a Final Fantasy-esque series with many more games. “We just didn’t see eye-to-eye with management,” he said, joking that the statute of limitations was probably up on the argument. “I went and fought for it, and I officially lost the battle.”

Yūji Horii, on the other hand, never cared to work on a Chrono Trigger sequel. “Since everything I would like to do can be done in a Dragon Quest title,” he told 1UP.com in 2005, “the chances of me making a sequel to Chrono Trigger are unlikely.”

Even though the Dream Team never returned to Chrono Trigger, it still served as inspiration for some of their future games. Many people consider Hironobu Sakaguchi’s 2006 Xbox 360 game Blue Dragon to be his take on the Dragon Quest series, but he revealed in a 2007 issue of Electronic Gaming Monthly that he considers it his follow-up to Chrono Trigger.

Indie games developer Simon S. Andersen, known for side-scrolling exploration game Owlboy, gave fans a tantalizing look at an alternative world where the Chrono series continued when he released a mockup trailer for Chrono Break in 2018. The trailer featured gorgeous pixel art graphics recalling Chrono Trigger’s classic Toriyama look with elements from Chrono Cross, blended into a cruel glimpse of what might have been. Or perhaps it’s a hopeful look at what could be, if only a party of enterprising youths find a way to travel back in time and twist the right dials at Square headquarters.

To Far Away Times

When Chrono Trigger released in 1995, Japanese RPGs were on the verge of breaking out in a huge way. It was not only a celebration of the 16-bit era, but a presage of the things to come as Square ignited the genre through the late ’90s and beyond with the release of Final Fantasy VII. Since then, Chrono Trigger has earned near mythological status among fans.

While they clamour for a remake in the style of 2020’s Final Fantasy VII Remake or a new release in the series, Robert Boyd suggests recapturing the magic isn’t quite as simple as it seems. “If you want another Chrono Trigger now, it can’t just be a copy of Chrono Trigger,” he told me. “It needs to be its own thing. One of the key things to Chrono Trigger’s success was how fresh it felt at the time; you can’t get that by just slavishly trying to copy it.”

Chrono Trigger is so many things. It’s whimsical and warm, tense, exhilarating, and thoughtful. It’s brisk and endlessly replayable, it’s bright and vibrant, its music gorgeous, its sprite art masterful. Chrono Trigger epitomizes the first golden age of JRPGs popularized by Dragon Quest and Final Fantasy in the ‘80s.

Chrono Trigger is timeless.

For 25 years, fans have looked to recapture the magic they first experienced playing Chrono Trigger in the glow of their CRTs, wishing to go back to those early days when the JRPG genre was finding its footing in western gaming culture. But Masato Kato sees it differently. “I have the following principle;” he said in a 2015 interview with Mariela Gonzalez, “the past is the past, and it should be left behind. You have to let go. To lay new foundations. To move on.”

In December, 2019, with Chrono Trigger’s 25th anniversary looming, I tried to rewind time. I popped my original cartridge into my childhood Super Nintendo, and started a New Game + playthrough using the save file I’d built over a dozen playthroughs as a kid. Channeling my inner 12 year old with a bag of five cent candy, a day of zero responsibilities, and a determination not to throw up this time, I made quick work of the Millennial Fair, traveled back to 600 AD, met with Frog, shifted to a more comfortable sitting position and… accidentally nudged my Super Nintendo with my foot.

The screen went black, but the music kept playing. Mitsuda’s iconic “Frog’s Theme” triumphantly backed my panic. I reset my console. The swinging pendulum. I pressed “Start.”

My childhood save was gone. The past was gone.

My cartridge cried out for a new adventure —

“Crono…”

Just like it did 25 years ago, when I first inserted it into the very same Super Nintendo —

“Crono!”

I think Kato would approve.

“Good morning, Crono!”

Aidan Moher is a Hugo-winning writer from Vancouver Island, BC. His work has appeared on Tor.com, Kotaku, and VentureBeat, and he’s the editor of Astrolabe — a newsletter about SFF and gaming. You can also find him on Twitter or his website.

All pixel art in this piece provided by The Spriters Resource